The Front Room ‘Inna Joburg’

Growing up in the 1970s, memories of witnessing the racist violence of the apartheid regime in South Africa on television never left McMillan, and when he was invited to Johannesburg to curate an iteration of The Front Room installation they came flooding back. This was through his brethren, Vanley Burke, the Birmingham-based Jamaican photographer, who was in South Africa and recommended The Front Room to Leora Farber-Blackbeard, the white female director of the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD) at the University of Johannesburg (UJ). McMillan’s subsequent connection with Leora, resulted in a two-month artist residency in Johannesburg (June-August 2016), during which The Front Room ‘Inna Joburg’ was created as an installation-based exhibition at the FADA Gallery, and complemented thematically by The Arrivants, a mixed-media installation created by the Black British artist-designer-academic Christine Checinska that explored the post-war Caribbean migrant narrative through the material culture of their dress.

Under apartheid, the Group Areas Act of 1950, racially segregated communities through the ‘forced removal’ of Black, Indian and Coloured (of mixed heritage) communities to ‘townships’ and ‘homelands’ outside Johannesburg. In the city, the vibrant Black cultural hub of Sophiatown was destroyed, and families removed to Soweto; Indian families were removed from the multi-cultural area of Fietas to Lenasia, and Coloured families removed to El Dorado Park. Moreover, the ‘pass laws’ separated and fractured families. In post-apartheid South Africa, a Black middle class has grown exponentially, but a Black majority still live in poverty, and African migrants from across the continent are targets of communal violence. The trauma of apartheid’s violence still casts a shadow in Johannesburg, which meant that working peripatetically with local communities, gathering oral histories, sourcing materials and archival images, would be much more challenging than developing previous iterations.

Before arriving in Johannesburg, McMillan liaised with VIAD, and from their team, Maria Fidel Regueros began informal interviews with Indian and Coloured respondents in Lenasia and Eldorado Park respectively. But VIAD’s staff were middle-class white females, and with the best intentions, they were outsiders, which only served to perpetuate the white privilege of post-apartheid. Rather than falsely ‘re-present’ these communities without even meeting them, it was agreed with VIAD that from an ethical and pragmatic perspective, it would be best to use The West Indian Front Room as model for the new installation, because he knew this from previous iterations.

With my guidance, Maria and Claire Jorgensen, also from the VIAD team, were able to source materials from The Cottage Hire, which hired out props for film and television shoots since the apartheid era where white television viewers would have had Black people working as maids and servants in their homes. In an uncanny way, the front room installation McMillan curated would be strangely familiar in white homes. Clearly, the Empire travels, because it was the colonial elite, who recreated a romantic version of an English in South Africa, just as they did in the Caribbean. McMillan didn’t want The Front Room ‘Inna Joburg’ to be an imitation of The West Indian Front Room, but rather a hybrid intervention to explore what was similar and different across the diaspora as he had done with previous iterations.

McMillan was under no illusion that coming from the UK, he would be viewed in Johannesburg as a tourist; a Black man with the privilege to travel internationally. Moreover, McMillan’s complexion from mixed African, Indian, Scottish, Portuguese ethnic heritage, would racially catergorise me as ‘Coloured’. He was also associated with University of Johannesburg with its inherited history of apartheid, from its processor institution Rand Afrikaans University. McMillan rented an apartment in Melville, nearby the Auckland Park Campus of UJ where he was based, from a young white couple, who had an adjoining apartment and shared a low fenced back garden that was patrolled by three fully grown Rottweiler dogs, who looked like they could eat him. Melville is a ‘gated community’ with walled compounds surrounded by electrified fences and private security guards patrolling the streets, because the police couldn’t be trusted. This was nothing new to McMillan coming from Hackney, and in moving around Johannesburg, he was similarly street-wise.

On the rare occasions McMillan saw my landlords, they would invite him to have dinner with them, though a Black fellow artist, who knew them, said that they didn’t have Black people in their home. This was strange, because he saw a Black woman cleaning their apartment every day. McMillan’s colleague told me that a Black maid in South Africa was not considered human, and therefore qualify as a Black person entering their home. Unsurprisingly, the dinner with McMillan’s landlord’s never materialised.

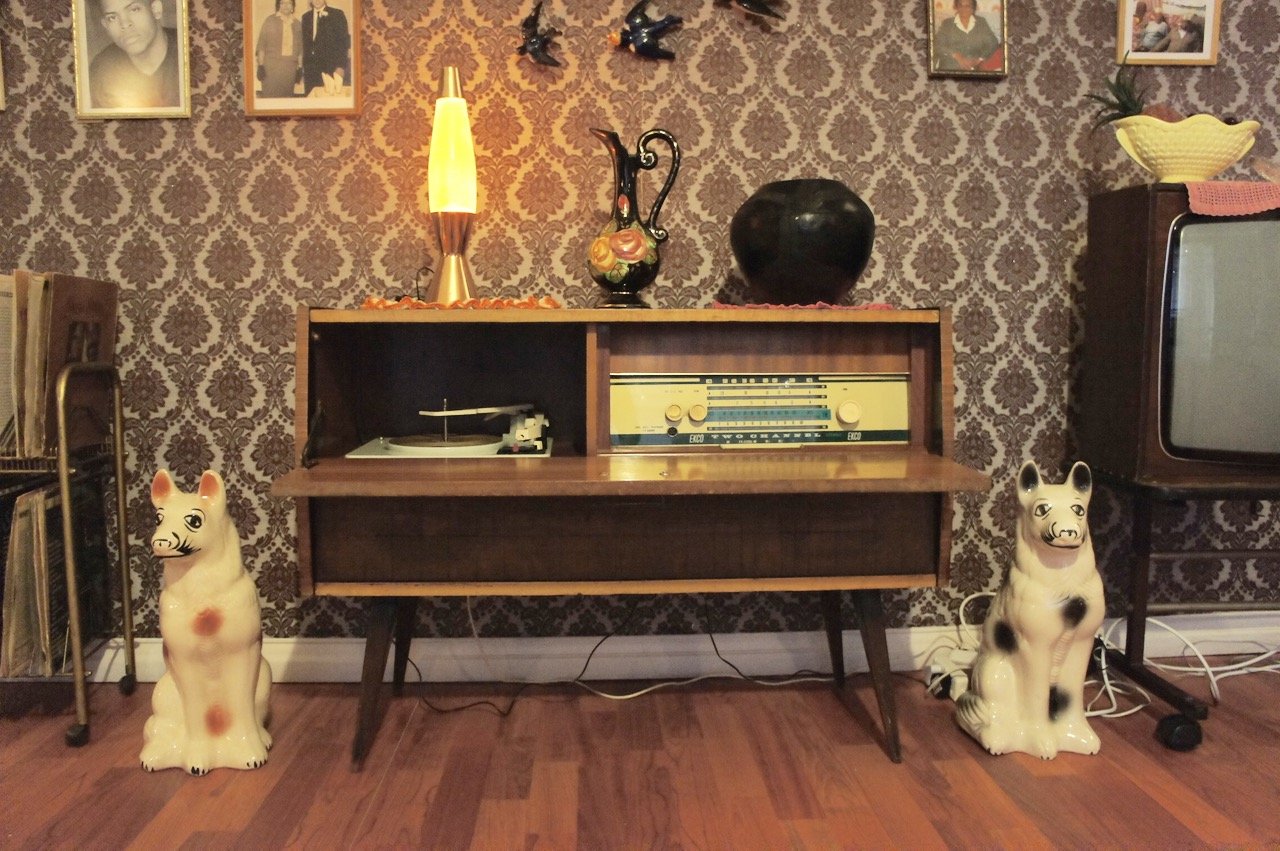

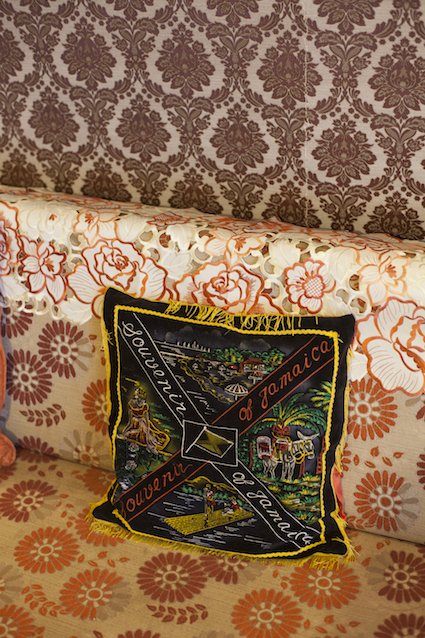

The furniture, fixtures, appliances, soft furnishings, ornaments and wall hangings in The Front Room ‘Inna Joburg’ installation were consistent with The West Indian Front Room. McMillan also brought some of my mum’s iron-starched crochet doilies and other soft furnishings from the UK, as well as framed portraits of his immediate family, rather than images of people he didn’t know. Wall hangings of a painted portrait of Nelson Mandela juxtaposed with a chrome etching of Queen Elizabeth II visually subverted what one might see in a typical white South African home.

In honour of McMillan’s canine friends at home, two ceramic dogs stood guard either side of a radiogram, and on the top, a clay bowl traditionally used by South African Venda women to make homemade beer, as a means of supplementing their income. From the radiogram, could be heard of a playlist of music that included Pata Pata (1957), by the Black South African singer, Miriam Makeba, who on a tour of the United States was asked in an interview how she compared the USA with South Africa. She said that while the United States hid it system of apartheid, they didn’t in South Africa.

Maria took McMillan to visit the Indian and Coloured respondents she had interviewed initially, and Shonisani ‘Shoni’ Maphangwa, a post-graduate researcher and lecturer at UJ, took him to meet a number of Black women, including her mother in Soweto. They subsequently participated in an oral history workshop in the FADA gallery, where they shared stories about a cherished object they had brought from their homes. Many of these women had been domestic maids in middle class white homes, which reminded McMillan of his mum working for six years as a maid for a Dutch family in Curacao, before coming England. She put ‘seamstress’ as her occupation in her passport, and she like these women, learnt to crochet. One woman’s story struck him. She had an abusive husband, who took all the money she earned from her day job. So to feed her five children, she made colourful crochet doilies at night and sold them during the day.

It was these encounters with individuals that McMillan found the most enriching, such as Simphiwe Buthelezi, a young Black woman studying Fine Art, who took images of her interventions in the installation and included here. He also invited the Black security and cleaning staff to see the installation, where they shared a cultural practice about the importance of Sunday dinner having seven colours from different food.

In Jacob Dlamini’s Native Nostalgia he recalls the material life of his youth in the township including the summer of 1976, when Black students rose up in Soweto, against what they saw as the complacency of their parents towards state-legitimised oppression. That same summer, was McMillan’s first time at the Notting Hill Carnival, where Black youth, who did not share the same values as their Caribbean migrant parents, revolted against police brutality.